Hastāmalaka Stotram

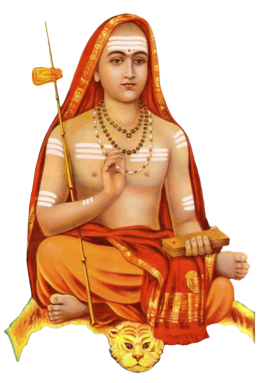

Composed by Hastāmalaka Ācārya, a direct disciple of Adi Sankaracharya, the Hastāmalaka Stotraṁ is a short Vedāntic text about the higher nature of the Self.

Hastāmalaka Stotram

Hasta-āmalaka is meant to be ‘an amla berry (āmalakam) in the hand (hasta)’. Śaṅkarācārya used this berry as a metaphor to acknowledge Hastāmalaka’s ‘ripeness’ and his clarity of knowledge regarding Vedānta, and also to reveal the esoteric nature of the Vedāntic scriptures as a whole (to reveal knowledge that is ‘hidden’). Ādi Śaṅkarācārya had four primary, direct disciples whose works survive to the present day; Sureśvara, Padmapāda, Toṭaka and Hastāmalaka. Though numerous texts are available for study by Sureśvara, only this particular work by Hastāmalaka has survived.

It is believed that Hastamalaka was just seven years old when he narrated these 12 verses, in response to a question from Shankara. This remarkable story is detailed below. Shankara himself was compelled to write a commentary on the Hastamalakiyam. It is extraordinary that the master of masters would compose commentary upon the work of his young student.

An introduction to Hastamalakiyam

Hastāmalakiyam Verses - In Sanskrit and English with Meaning and Commentary by Adi Sankaracharya

Hastamalaka – Intro A

Hastamalaka – Intro B

Hastamalaka-1-bhujaṅgaprayāta

Hastamalaka-2-yamagnyuṣṇavan

Hastamalaka-3-mukhābhāsako

Hastamalaka-4-yathā darpaṇābhāva

Hastamalaka-5-manaścakṣur

Hastamalaka-6-ya eko vibhāti

Hastamalaka-7-yathā’nekacakṣuḥ

Hastamalaka-8-vivasvat

Hastamalaka-9-yathā sūrya

Hastamalaka-10-ghanacchannadṛṣṭir

Hastamalaka-11-samasteṣu

Hastamalaka-12-upādhau yathā

Introduction - English Translation of Sri Sankara Bhashya by S.N. Sastri

It is well known that Sri Sankaracharya had four disciples, one of whom was named Hastamalaka. This was not his original name, but was given to him by the Acharya. How he became a disciple of Sri Sankara is described beautifully in the work entitled ‘Sankara-Digvijaya’ by Swami Vidyaranya. It is said therein that during his stay at the famous temple at Mookambika the Acharya happened to visit a nearby village named Sri Bali. In that village there was a Brahmana by name Prabhakara who was noted for his learning and the regular performance of the rites enjoined by the Vedas. Though he was quite wealthy and was respected by all, he was not happy because his only son was dumb and behaved like a congenital idiot. On hearing that the great Acharya had come to his village, he decided to take his son to the Acharya in the hope that the latter’s blessing would cure his child and make him a normal, intelligent boy. He went to the Acharya and prostrated before him and asked his son to do the same. The boy prostrated, but did not get up for quite a long time. The Acharya, in his unbounded compassion, lifted up the boy. The father then told the Acharya, “O Sir, this boy is now seven years old, but his mind is totally undeveloped. He has not learnt even the alphabets, not to speak of the Vedas. Boys of his age come and call him to join them in play, but he does not respond. If they beat him he remains unaffected. Sometimes he takes some food, but sometimes he does not eat at all. I have completely failed in my efforts to teach him”. When the father had said this, the Acharya asked the boy ”Who are you? Why are you behaving in this strange manner, as if you are an inert thing?” To this the boy replied, “I am certainly not an inert thing. Even an inert thing becomes sentient in my presence. I am of the nature of infinite Bliss, free from the six waves (hunger, thirst, grief, delusion, old age and death) and the six stages (birth, existence, growth, change, decay and destruction)”. The boy then expounded the gist of all the Upanishads in twelve verses, which became famous under the name ‘Hastamalakiyam’ or ‘Hastmalaka Stotram’. As the knowledge of the Atman was as clear to him as an amalaka fruit in one’s palm, the name “Hastamalaka” was given to him.

The Acharya then told the father of the boy “This apparently dumb son of yours knows the truth of the Atman by virtue of his practices in past lives. He is totally free from all attachment and any sense of I-ness with regard to the body. Let this boy come with me”. So saying, the Acharya took the boy along with him as his disciple.

Subsequently, while explaining to his other disciples how this boy had attained Self-knowledge even at this very young age, Sri Sankara says, “One day, when he was a two-year old child, his mother had taken him along with her when she went to the river for her bath. She left the child on the bank under the care of a Jnani who happened to be sitting there. The child accidentally fell into the water when the Jnani was deep in meditation. When the mother came back after her bath she was shocked to find that the child was dead and she began to cry. Moved by pity for her the Jnani, by virtue of his Yogic power, entered the body of the child, casting off his own mortal coil. The child thus became a realized soul.

Sri Sankara was so impressed by the profundity of these twelve verses that he himself wrote an elaborate commentary on them. In this commentary Sri Sankara refers to Hastamalaka, his own disciple, as the ‘Acharya’. This indicates, not only the greatness of Hastamalaka’s verses, but also the magnanimity of the Guru, Sri Sankara. The explanation of these twelve verses, given in the following paragraphs, is based on Sri Sankara’s commentary.

Sri Sankara, at the commencement o his commentary on Hastamalakiyam, says that the desire o every living being on this earth is to enjoy happiness all the time and to be always free from sorrow. The activities of all creatures are directed towards achieving these two objectives. But a rare human being, who has accumulated an abundant store of punya [merit] in past lives, realizes that all happiness derived from sense-objects is transitory and is bound to be followed by sorrow. As a result, he develops total detachment towards all sense pleasures and strives to bring an end to Samsara, the continuous cycle o birth and death. Since ignorance of one’s Self (Atma) is the root cause of Samsara and only Self-knowledge can put an end to Samsara, Hastamalaka, referred to here by Sri Sankara as the ‘Acharya’, teaches Self-knowledge in the following twelve verses.