सांख्ययोग

Sankhya Yoga - The Yoga of Knowledge

Arjuna acknowledges in the opening few verses that he is confused about his duty and surrenders to the Lord to instruct him about what is good for him. Thereafter, the Lord begins His teaching and by the end of the chapter, we get an exhaustive summary of the entire philosophical content of the Gita. Below are the main themes of Chapter 2:

Verses 1 - 10

Arjunaśaraṇāgati - Arjuna realizes the depth of his problem and knows he cannot solve it by himself. These verses describe Arjuna's attitude of surrender towards his Guru, Lord Krishna.

Verses 11 - 38

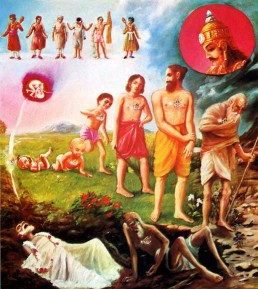

Sāṅkhya-Yoga - Lord Krishna expounds the highest knowledge about the nature of the immortal Self and the impermanence of all other things, including the body and the world.

Verses 39 - 53

Karma-Yoga - Lord Krishna stresses the importance of doing one's duty and the way to perform such duty, the way to be a true Karma Yogi through discrimination, dispassion, equanimity and skill in action. Then he glorifies Karma Yoga as a way to come to Sankhya Yoga.

Verses 54 - 72

Sthitaprajñatva-upāya and Sthitaprajña-lakṣaṇa - The Lord describes the characteristics of the one who is firmly established in the Self (Sthitaprajña) and highlights the Sadhanas or practices required to attain such a state, where one lives as a Jivan Mukta.

Gita Chapter 2 - 72 Verses

Srimad Bhagavad Gita - Chapter 2 - 72 Verses

Commentary by Swami Paramarthananda

Background

In the first chapter, Arjuna was shown to be completely immersed in grief (śoka) caused by attachment (rāga) and delusion (moha). Independently analyzing the problem, he comes to the conclusion that withdrawing from the war is the only solution.

In the beginning of the second chapter we see the turning point in Arjuna. Chastised by Kṛṣṇa

(2, 3), Arjuna analyses the situation further. This leads to the two important discoveries:

1. His weakness of attachment is a fundamental problem which cannot be solved by superficial methods (9).

2. He has to surrender completely to a guru to get out of this fundamental problem (8).

Thus, Arjuna becomes a śiṣya by surrendering to Lord Kṛṣṇa. Naturally, Kṛṣṇa also becomes a guru. Now that the guru-śiṣya relationship has been struck, the teaching can begin (10).

[Once a human being discovers a seeker in him, the guru will be right in front. The vedaantic teaching can take place only between a guru and śiṣya.]

Kṛṣṇa straightway attacks Arjuna’s idea that war is going to harm Bhīṣma or himself. He points out that all the problems of Arjuna are because of delusion caused by ignorance, for wise men never have a problem (11). Thereafter, Kṛṣṇa gives different reasons to establish that Arjuna has to fight this war:

- From the stand point of true nature of Ātmā (ādhyātmika-dṛśṭi), Bhīṣma and others are immortal. Ātmā is never subject to changes in spite of the changes of the body. It is neither a doer nor an enjoyer. Hence, neither is Arjuna a slayer nor is Bhīṣma slain. So, why should he resist to fight? (12 to 25). Even if the Ātmā is impermanent, Arjuna should not lament. Whatever appears will have to disappear and whatever disappears will appear. Hence, one should learn to accept the change. [In fact, change is the beauty of the creation. It looks ugly when our outlook is partial or selfish.] Hence, why should Arjuna grieve for the physical separation from Bhīṣma and others which is inevitable in life? (26 to 30).

- From the stand point of Kṣatriya’s duty (dhārmika-dṛśṭi), Arjuna can fight if it is necessary to establish order. A kṣatriya must look at the problem not from personal stand point, but from social stand point (31). Hence, why should Arjuna hesitate to fight for a righteous cause? A righteous war is a door to heaven for a kṣatriya (32). If Arjuna avoids war, not only he be shirking his duty and losing heaven, but he will positively incur sin (33). For avoiding sin, at least, Arjuna should fight.

- Looking at the situation from worldly angle (laukika-dṛśṭi), Arjuna should not withdraw from the war. He will be called a coward by everyone (including the future generation) (34, 36). Shouldn’t Arjuna fight to protect his reputation?

With these arguments, Lord persuades Arjuna to fight (37, 38) and concludes the first part of his teaching. He calls this sāṅkhya-yoga (39). [In fact, the first argument which deals with the nature of the Ātmā and the body (ātma-anātma-viveka) alone is the sāṅkhya-yoga.] Hereafter, the Lord enters into buddhi-yoga (karma-yoga). [Though sāṅkhya-yoga is the true solution for sorrow, many are not fit to gain

it because of the false idea (moha) that worldly pursuits can solve the problem. So, initially, one has to be allowed to pursue worldly ends. By this, one should discover for oneself that actions and their results cannot give permanent satisfaction. This is dispassion. A dispassionate mind can pursue sāṅkhya-yoga. Thus karma-yoga is introduced as a means to come to sāṅkhya-yoga.]

First, the Lord describes the glory of karma-yoga (40 to 46). Then comes the principle of karma-yoga. One can choose one’s action but never the result. The result is dependent on the laws of action. The other factors of the world, known and unknown, may bring a totally unexpected result. One cannot avoid that. Yet inaction will not be a solution (47). No one can completely know the laws of action. Hence, actions are often imperfect in spite of effort. So, one should ever be ready for any result. One can hope for the best, but should be prepared for the worst. When one acts with the above understanding, success and failure lose their capacity to shake him. One does not react, because he is not caught unawares. This equanimity in action is yoga (48). Thus, one can convert the binding karma into a valid teacher. This is skill in action (50). A tranquil mind will soon shed its false value attributed to the world and turns towards the Ātmā (52). When, through Self-knowledge, one gets established in the peaceful Ātmā, he attains liberation (53).

Now, Arjuna becomes curious to know the characteristics of a person who is firmly established in Self-knowledge (sthitaprajña) (54). Kṛṣṇa answers Arjuna’s question and gives the means of stabilizing the knowledge.

Knowledge cannot be fruitful unless it is stabilized and assimilated. For this, Kṛṣṇa talks about two important sādhanas (58 to 68). They are the control of the mind and the sense organs and contemplation upon the teaching. By this, the knowledge sets (61). On the other hand, if these are not practiced, the mind and the sense organs will drag a person to the field of sense objects and gradually pull him down spiritually (62, 63).

Talking about the characteristics of a wise man, the Lord points out that the man of Self-knowledge is always satisfied with himself and consequently, he is free from all desires (55). He is independent of the world to be happy. Naturally, he is free from attachment, hatred, desire, anger, fear, elation, depression etc. (56, 57). Though living in the same world, he enjoys a freedom and contentment which is unknown to others. Thus, if the ignorant man can be said to be in darkness with regards to the Ātmā, the wise man is in broad daylight of the Ātmā

(69). The best comparison for the wise man’s mind is the ocean. The ocean is independently full and is unaffected by the rivers, entering or not entering, dirty or clean. Similarly, the wise man’s mind is independently full. It is undisturbed by the favourable and unfavourable experiences, entering or not entering (70). Kṛṣṇa concludes this topic by glorifying this state as the Brāhmī-state, reaching which one does not get deluded again. He lives life as a jīvan-mukta (liberated while living) even at the far end of this journey. After death, he becomes one with Brahman (nirvāṇam) which is called videha-mukti.

Thus the second chapter discusses the following four topics mainly:

- Arjunaśaraṇāgati: 1 to 10

- Sāṅkhya-yoga: 11 to 38

- Karma-yoga: 39 to 53

- Sthitaprajñatva-upāya and sthitaprajña-lakṣaṇa: 54 to 72

Since sāṅkhya-yoga is the main topic, this chapter is aptly called Sāṅkhya-yoga.