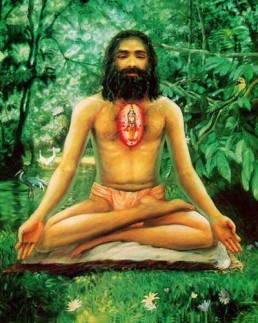

Patanjali Yogasutra Introduction

Part 1 – Samādhi-pāda – Yoga and its Aims

1.1

1.2

1.3

1.4

1.5

1.6

1.7

1.8

1.9

1.10

1.11

1.12

1.13

1.14

1.15

1.16

1.17

1.18

1.19

1.20

1.21

1.22

1.23

1.24

1.25

1.26

1.27

1.28

1.29

1.30

1.31

1.32

1.33

1.34

1.35

1.36

1.37

1.38

1.39

1.40

1.41

1.42

1.43

1.44

1.45

1.46

1.47

1.48

1.49

1.50

1.51

Part 2 – Sādhana-pāda – Yoga and its Practice

2.1

2.2

2.3

2.4

2.5

2.6

2.7

2.8

2.9

2.10

2.11

2.12

2.13

2.14

2.15

2.16

2.17

2.18

2.19

2.20

2.21

2.22

2.23

2.24

2.25

2.26

2.27

2.28

2.29

2.30

2.31

2.32

2.33

2.34

2.35

2.36

2.37

2.38

2.39

2.40

2.41

2.42

2.43

2.44

2.45

2.46

2.47

2.48

2.49

2.50

2.51

2.52

2.53

2.54

2.55

Part 3 – Vibhūti-Pāda – Powers

3.1

3.2

3.3

3.4

3.5

3.6

3.7

3.8

3.9

3.10

3.11

3.12

3.13

3.14

3.15

3.16

3.17

3.18

3.19

3.20

3.21

3.22

3.23

3.24

3.25

3.26

3.27

3.28

3.29

3.30

3.31

3.32

3.33

3.34

3.35

3.36

3.37

3.38

3.39

3.40

3.41

3.42

3.43

3.44

3.45

3.46

3.47

3.48

3.49

3.50

3.51

3.52

3.53

3.54

3.55

3.56

Part 4 – Kaivalya-pāda – Liberation

4.1

4.2

4.3

4.4

4.5

4.6

4.7

4.8

4.9

4.10

4.11

4.12

4.13

4.14

4.15

4.16

4.17

4.18

4.19

4.20

4.21

4.22

4.23

4.24

4.25

4.26

4.27

4.28

4.29

4.30

4.31

4.32

4.33

4.34

Commentary on Sri Patanjali Yogasutra by Swami Vivekananda

This is, again, Sankhya philosophy. We have seen from the same philosophy that from the lowest form up to intelligence all is nature; beyond nature are Purushas (souls), which have no qualities. Then how does the soul appear to be happy or unhappy? By reflection. If a red flower is put near a piece of pure crystal, the crystal appears to be red, similarly the appearances of happiness or unhappiness of the soul are but reflections. The soul itself has no colouring. The soul is separate from nature. Nature is one thing, soul another, eternally separate. The Sankhyas say that intelligence is a compound, that it grows and wanes, that it changes, just as the body changes, and that its nature is nearly the same as that of the body. As a finger-nail is to the body, so is body to intelligence. The nail is a part of the body, but it can be pared off hundreds of times, and the body will still last. Similarly, the intelligence lasts aeons, while this body can be “pared off,” thrown off. Yet intelligence cannot be immortal because it changes — growing and waning. Anything that changes cannot be immortal. Certainly intelligence is manufactured, and that very fact shows us that there must be something beyond that. It cannot be free, everything connected with matter is in nature, and, therefore, bound for ever. Who is free? The free must certainly be beyond cause and effect. If you say that the idea of freedom is a delusion, I shall say that the idea of bondage is also a delusion. Two facts come into our consciousness, and stand or fall with each other. These are our notions of bondage and freedom. If we want to go through a wall, and our head bumps against that wall, we see we are limited by that wall. At the same time we find a will power, and think we can direct our will everywhere. At every step these contradictory ideas come to us. We have to believe that we are free, yet at every moment we find we are not free. If one idea is a delusion, the other is also a delusion, and if one is true, the other also is true, because both stand upon the same basis — consciousness. The Yogi says, both are true; that we are bound so far as intelligence goes, that we are free so far as the soul is concerned. It is the real nature of man, the soul, the Purusha, which is beyond all law of causation. Its freedom is percolating through layers of matter in various forms, intelligence, mind, etc. It is its light which is shining through all. Intelligence has no light of its own. Each organ has a particular centre in the brain; it is not that all the organs have one centre; each organ is separate. Why do all perceptions harmonise? Where do they get their unity? If it were in the brain, it would be necessary for all the organs, the eyes, the nose, the ears, etc., to have one centre only, while we know for certain that there are different centres for each. Both a man can see and hear at the same time, so a unity must be there at the back of intelligence. Intelligence is connected with the brain, but behind intelligence even stands the Purusha, the unit, where all different sensations and perceptions join and become one. The soul itself is the centre where all the different perceptions converge and become unified. That soul is free, and it is its freedom that tells you every moment that you are free. But you mistake, and mingle that freedom every moment with intelligence and mind. You try to attribute that freedom to the intelligence, and immediately find that intelligence is not free; you attribute that freedom to the body, and immediately nature tells you that you are again mistaken. That is why there is this mingled sense of freedom and bondage at the same time. The Yogi analyses both what is free and what is bound, and his ignorance vanishes. He finds that the Purusha is free, is the essence of that knowledge which, coming through the Buddhi, becomes intelligence, and, as such, is bound.

Yogasutra – Verse 2.20 – Yogasutra-2.20-draṣṭā dṛśimātraḥ – In Sanskrit with English Transliteration, Translation, Meaning and Commentary by Swami Vivekananda – Yogasutra-2-20