Ulladu Narpadu

உள்ளதல துள்ளவுணர் வுள்ளதோ வுள்ளபொரு

ளுள்ளலற வுள்ளத்தே யுள்ளதா – லுள்ளமெனு

முள்ளபொரு ளுள்ளலெவ னுள்ளத்தே யுள்ளபடி

யுள்ளதே யுள்ள லுணர்வாயே – யுள்ளே

Uḷḷa-dala duḷḷa-vunar uḷḷadō vuḷḷa-porul

Uḷḷa-laṛa vuḷḷatē uḷḷa-dāl – uḷḷa-menum

Uḷḷa-poruḷ uḷḷalevan uḷḷattē uḷḷa-paḍi

Uḷḷadē uḷḷal uṇar-vāyē – uḷḷē

1. Unless Reality exists, can thought of it arise? Since, devoid of thought, Reality exists within as Heart, how to know the Reality we term the Heart? To know That is merely to be That in the Heart.

மரணபவ மில்லா மகேசன் – சரணமே

சார்வர்தஞ் சார்வொடுதாஞ் சாவுற்றார் சாவெண்ணஞ்

சார்வரோ சாவா தவர்நித்தர் – பார்வைசேர்

Maraṇa-bhava millā magēsan – chara-ṇamē

Sārvar-tañ sārvoḍu-tāñ savuṭṭṛār sāveṇṇañ

Sārvarō sāvā davar-nittar – pārvai sēr

நாமுலகங் காண்டலா ணாணாவாஞ் சத்தியுள

வோர்முதலை யொப்ப லொருதலையே – நாமவுருச்

சித்திரமும் பார்ப்பானுஞ் சேர்படமு மாரொளியு

மத்தனையுந் தானா மவனுலகு – கர்த்தனுயிர் 1

Nāmulagaṇ kāṇda-lāl nānāvān shakti-yula

Ōrmudalai oppal oru-talaiyē – nāma-vuru

Chittira-mum pār-pānum chērpaḍa-mum āroḷi-yum

Attanai-yun tānām avanulagu – karta nuyir [1]

மும்முதலாய் நிற்குமென்று மும்முதலு – மும்முதலே

யென்னலகங் கார மிருக்குமட்டே யாங்கெட்டுத்

தன்னிலையி னிற்ற றலையாகுங் – கொன்னே 2

Mummu-dalai niṛku-menḍṛu mummu-dalum – mum mudalē

Yennal-ahaṇ kāram irukku-maṭṭē yān-keṭṭu

Tannilai-yil niṭṭral talai-yāguṅ – konnē [2]

றுலகுசுக மன்றென் றுரைத்தெ – னுலகுவிட்டுத்

தன்னையோர்ந் தொன்றிரண்டு தானற்று நானற்ற

வந்நிலையெல் லார்க்குமொப் பாமூனே – துன்னும் 3

Ulagu-sukam anḍṛen ḍṛurait-ten – ulagu-viṭṭu

Tannai-yōrn donḍṛi-raṇḍu tānaṭṭṛu nānaṭṭṛa

Annilai-yel lārkkum oppā-mūnē – tunnum [3]

முருவந்தா னன்றே லுவற்றி – னுருவத்தைக்

கண்னுறுதல் யாவனெவன் கண்ணலாற் காட்சியுண்டோ

கண்ணதுதா னந்தமிலாக் கண்ணாமே – யெண்ணில் 4

Uruvan-tān anḍṛēl uvaṭṭrin – uruvat-tai

Kaṇṇuṛu-dal yāva-nevan kaṇṇalār kāṭchi-yuṇdō

Kaṇṇadu-tān anda-milā kaṇṇāmē – yeṇṇil [4]

முடலென்னுஞ் சொல்லி லொடுங்கு – முடலண்றி

யுண்டோ வுலக முடல்விட் டுலகத்தைக்

கண்டா ருளரோ கழறுவாய் – கண்ட 5

Uḍal-ennuñ chollil oḍuṅ-gum – uḍal-anḍṛi

Uṇḍō ulagam uḍalviṭ ṭulagat-tai

Kaṇḍār uḷarō kazhaṛu-vāi – kaṇḍa [5]

புலனைம் பொறிக்குப் புலனா – முலகைமன

மொன்றைம் பொறிவாயா லோர்ந்திடுத லான்மனத்தை

யன்றியுல குண்டோ வறைநேரே – நின்ற 6

Pula-naim poṛik-kup pula-nām – ulagai-manam

Onḍṛaim poṛi-vāyāl ōrindiḍu-da lānma-nattai

Anḍṛi ulaguṇḍō aṛai-nērē – ninḍṛa [6]

முலகறிவு தன்னா லொளிரு – முலகறிவு

தோன்றிமறை தற்கிடனாய்த் தோன்றிமறை யாதொளிரும்

பூன்றமா மஃதே பொருளாமா – லேன்றதாம் 7

Ulaga-ṛivu tannāl oḷirum – ula-gaṛivu

Tōnḍṛi-maṛai taṛkiḍa-nāyt tōnḍṛi-maṛai yā-doḷirum

Pūnḍṛa mā mahḍē poru-ḷāmā – lēnḍṛa-dām [7]

லப்போருளைக் காண்வழிய தாயினுமம் – மெய்ப்பொருளி

னுண்மையிற்ற னுண்மையினை யோர்ந்தொடுங்கி யொன்றுதலே

யுண்மையிற் காண லுணர்ந்திடுக – விண்மை 8

Appo-ruḷai kāṇ-vazhiya dāyinu-mam – meip-poruḷin

Uṇmaiyil-tan uṇmai-yinai ōrndo-ḍuṅgi onḍṛu-dalē

Uṇmaiyiṛ kānal uṇarn-diḍuga –viṇmai [8]

யிருப்பவா மவ்வொன்றே தென்று – கருத்தினுட்

கண்டாற் கழலுமவை கண்டவ ரேயுண்மை

கண்டார் கலங்காரே கானிருள்போன் – மண்டும் 9

Irup-pavām avvon-ḍṛē denḍṛu – karut-tinuḷ

Kaṇḍār kazhalu-mavai kaṇḍa varē uṇmai

Kaṇḍār kalaṅ-gārē kāṇiruḷ pōl – maṇḍum [9]

அறியாமை யின்றாகு மந்த – வறிவு

மறியா மையுமார்க்கென் றம்முதலாந் தன்னை

யறியு மறிவே யறிவா – மறிப 10

Aṛi-yāmai inḍṛā-gum anda – aṛivum

Aṛiyā maiyu-mārkken ḍṛam-mudalān tannai

Aṛi-yum aṛivē aṛi-vām –aṛiba [10]

யறிவ தறியாமை யன்றி – யறிவோ

வறிவயற் காதாரத் தன்னை யறிய

வறிவரி யாமை யறுமே – யறவே 11

Aṛiva daṛi-yāmai anḍṛi – aṛivō

Aṛi-vayaṛ kādārat tannai aṛiya

Aṛi-vaṛi yāmai aṛumē – aṛavē [11]

மும்முதலாய் நிற்குமென்று மும்முதலு – மும்முதலே

யென்னலகங் கார மிருக்குமட்டே யாங்கெட்டுத்

தன்னிலையி னிற்ற றலையாகுங் – கொன்னே 12

Mummu-dalai niṛku-menḍṛu mummu-dalum – mum mudalē

Yennal-ahaṇ kāram irukku-maṭṭē yān-keṭṭu

Tannilai-yil niṭṭral talai-yāguṅ – konnē [12]

ஞானமாம் பொய்யாமஞ் ஞானமுமே – ஞானமாந்

தன்னைன்றி யின்றணிக டாம் பலவும் போய்மெய்யாம்

பொன்னையன்றி யுண்டோ புகலுடனா – னென்னுமத் 13

Jñāna-mām poiyām-añ jñāna-mumē – jñāna-mān

Tannai-anḍṛi yinḍṛaṇi-gal ṭām-palavum poimei-yām

Ponnai-yanḍṛi-uṇdō pugaluḍa-nān – ennumat [13]

தன்மையி னுண்மையைத் தானாய்ந்து – தன்மையறின்

முன்னிலைப படர்க்கை முடிவுற்றொன் றாயொளிருந்

தன்மையே தன்னிலைமை தானிதமு – மன்னும் 14

Tanmai-yin uṇmai-yai -tānāindu – tanmai-yaṛin

Munnilai paḍark-kai mudivuṭ-ṭṛōnḍṛāi yoḷirum

Tanmaiyē tannilai-mai tānida-mum – mannum [14]

நிகழ்கா லவையு நிகழ்வே – நிகழ்வொன்றே

யின்றுண்மை தேரா திரப்பெதிர்வு தேர்வுன

லொன்றின்றி யெண்ண வுனலுணர – நின்றபொருள் 15

Nigazh-kāl avaiyu nigazhvē – nigazh-vonḍṛē

Yinḍṛuṇ-mai tērā diṛap-pedirvu tēra-vunal

Onḍṛinḍṛi yeṇṇa unaluṇara – ninḍṛa-poruḷ [15]

னாமுடம்பே னாணாட்டு ணாம்படுவ – நாமுடம்போ

நாமின்றன் றென்றுமொன்று நாடிங்கங் கெங்குமொன்றால்

னாமுண்டு நாணாடி னாமூன – மாமிவ் 16

Nām-uḍambēl nāḷ-nāṭṭuḷ ṇām-paḍuvam – nām-uḍambō

Nām-inḍṛan ḍṛenḍṛu-monḍṛu nāḍiṅ-gaṅ gengu-moḍṛāl

Nām-uṇḍu nāṇāḍil nāmū-nam – āmiv [16]

குடலளவே நான்ற னுணரார்க் – குடலுள்ளே

தன்னுணர்ந்தார்க் கெல்லையறத் தானொளிரு நானிதுவே

இன்னவர்தம் பேதமென வெண்ணுவாய் – முன்னாம் 17

Uḍa-laḷavē nāntan uṇa-rārkku – uḍa-luḷḷē

Tannuṇarn-dārk kellai-yaṛa tānoḷirum nān-iduvē

Inna-vardam bhēda-mena eṇṇu-vāi – munnām [17]

குலகளவா முண்மை யுணரார்க் – குலகினுக்

காதார மாயுருவற் றாருமுணர்ந் தாருண்மை

யீதாகும் பேதமிவர்க் கெண்ணுக – பேத 18

Ulagaḷa-vām uṇmai uṇa-rārkku – ulagi-nukku

Ādāra maiuru-vaṭṭṛā rum-uṇarn dār-uṇmai

Īdā-gum bhēdam-ivark keṇṇuga – bhēda [18]

விதிமதி வெல்லும் விவாதம் – விதிமதிகட்

கோர்முதலாந் தன்னை யுணர்ந்தா ரவைதணந்தார்

சார்வரோ பின்னுமவை சாற்றுவாய் – சார்பவை 19

Vidi-madi vellum vivā-dam – vidi-madigaṭku

Ōrmuda-lān tannai uṇarn-dār avai-taṇandār

Chār-varō pinnu-mavai chāṭṭṛuvāi – chār-bhavai [19]

காணு மனோமயமாங் காட்சிதனைக் – காணுமவன்

றான்கடவுள் கண்டானாந் தன்முதலைத் தான்முதல்போய்த்

தான்கடவு ளன்றியில தாலுயிராத் – தான் கருதும் 20

Kāṇum manōmaya-māṇ kāṭchi-tanaik – kāṇu-mavan

Tānkaḍa-vuḷ kaṇḍā-nān tan-mudalai tān-mudalpōi

Tānkaḍa-vuḷ anḍṛi-yila dāl-uyirā – tān-karudum [20]

லென்னும்பன் னூலுண்மை யெனையெனின் – றன்னைத்தான்

காணலெவன் றானொன்றாற் காணவொணா தேற்றலைவற்

காணலெவ னூணாதல் காணவையுங் – காணும்

Ennum pannul-uņmai ennai-enin – tannait-tān

Kāṇal-evan tānond-ṛār kāṇa-voṇā dēṭtralai-var

Kāṇal-evan uṇādal kāṇ….

மதியினை யுள்ளே மடக்பதியிற்

பதித்திடுத லன்றிப் பதியை மதியான்

மதித்திடுத லெங்ஙன் மதிமதியிலதால் 22

Madi-yinai uḷḷē maḍakki – padiyil

Padittiḍu-dal anḍṛip padi-yai madi-yāl

Madit-tiḍu-dal eṅṅgan madi-yāi – madi-yiladāl [22]

நானின்றென் றாரு நவில்நானொன் –

றெழுந்தபி னெல்லா மெழுமிந்த நானெங்

கெழுமென்று நுண்மதியாநழுவும் 23

Nā-ninḍṛen ḍṛāru navil-vadilai – nān-onḍṛu

Ezhun-dapin ellām ezhu-minda nān-eṅgu

Ezhu-menḍṛu nuṇ-madiyāl eṇṇa – nazhu-vum [23]

துடலளவா நானொன் றுதமிடையிலிது

சிச்சடக்கி ரந்திபதஞ் சீவனுட்ப மெய்யகந்தை

யிச்சமு சாரமன மெண்ணெவிச்சை 24

Uḍal-aḷavā nānonḍ ṛudik-kum – iḍaiyi-lidu

Chit-jada granti-bhandam jīva-nuṭpa mei-yahandai

ichamu-sāra manam eṇṇ-ennē – vichai [24]

முருப்பற்றி யுண்டுமிக முருவிட்

டுருப்பற்றுந் தேடினா லோட்டம் பிடிக்கு

முருவற்ற பேயக்ந்தை யோர்கருவாம் 25

Urup-paṭṭṛi uṇḍu-miga vōṅgum – uru viṭṭu

Urup-paṭṭṛum tēḍi-nāl ōṭṭam piḍik-kum

Uru-vaṭṭṛa pēi ahandai ōrvāi – karuvām [25]

மகந்தையின் றேலின் றனைமகந்தயே

யாவுமா மாதலால் யாதிதென்று நாடலே

யொவுதல் யாவுமென வோர்முமேவுமிந்த 26

Ahan-dai inḍṛēl inḍṛa-naittum – ahan-daiyē

Yāvu-maam āda-lāl yādi-denḍṛu nāḍalē

Ovu-dal yāvu-mena ōrmudal-pol – mēvu-minda [26]

நானுதிக்குந் தானமதை னானுதியாத்

தன்னிழப்பைச் சார்வதெவன் சாராமற் றானதுவாந்

தன்னிலையி னிற்பதெவன் சாமுன்னர் 27

Nānudik-kum tāna-madai nāḍā-mal – nānudi-yā

Tannizhap-pai chārva-devan chā-rāmaṛ tānadu-vān

Tannilai-yil niṛpa-devan chāṭ-ṭṛudi – munnar [27]

விழுந்த பொருள்காண வமுழுகுதல்போற்

கூர்ந்தமதி யாற்பேச்சு மூச்சடக்கிக் கொண்டுள்ளே

யாழ்ந்தறிய வேண்டு மறிபிணதீர்ந்துடலம் 28

Vizhunda poruḷ-kāṇa vēṇḍi – muzhugu-dalpōl

Kūrnda-madi yāl-pēchu mūcha-ḍakki koṇ-ḍuḷḷē

Āzhn-daṛiya vēṇ-ḍum aṛipi-ṇampōl – tīrndu-ḍalam [28]

னானென்றெங் குந்துமென நஞானநெறி–

யாமன்றி யன்றிதுநா னாமதுவென் றுன்னறுணை

யாமதுவி சாரமா மாவமீமுறையே 29

Nā-nenḍṛeṅ gundu-mena nāḍu-dalē – jñāna-neri

Yāman-ḍṛi anḍṛi-dunā nāmadu-ven ḍṛunnal-tuṇai

Yāmadu vichāra-mā māva-danāl – mī-muṛaiyē [29]

நானா மவன்றலை நாணமநானானாத்

தோன்றுமொன்று தானாகத் தோன்றினுநா னன்றுபொருள்

பூன்றமது தானாம் பொருள்பதோன்றவே 30

Nānām avan-talai nāṇa-muṛa – nān-nānā

Tōnḍṛu-monḍṛu tānā-ga tōn-ḍṛinu-nān anḍṛu-poruḷ

Pūnḍṛa-madu tānām poruḷ poṅgi – tōn-ḍṛavē [30]

கென்னை யுளதொன் றியற்றுதற்குத் – தன்னையலா

தன்னிய மொன்று மறியா ரவர்நிலைமை

யின்னதென் றுன்ன லெவன்பரமாப் – பன்னும் 31

Ennai uḷa-don ḍṛiyaṭṭṛu-daṛkut – tannai-alādu

Anni-yam onḍṛum aṛiyār avar-nilaimai

Inna-den ḍṛunnal evan-paramāp –pannum [31]

யெதுவென்று தான்றேர்ந் ததுநா –

னிதுவென்றென் றெண்ணலுர னின்மையினா லென்று

மதுவேதா னாயமர்வ தாலே – யதுவுமலாது 32

Edu-venḍṛu tān tērndirādu – adu-nān

Iduvan-ḍṛen ḍṛeṇṇal-uran inmaiyi-nāl enḍṛum

Aduvē-tānāi yamarva dālē – aduvum-alādu [32]

னென்ன னகைப்புக் கிடனாகு – மென்னை

தனைவிடய மாக்கவிரு தானுண்டோ வொன்றா

யனைவரனு பூதியுண்மை யாலோர் – நினைவறவே 33

Enna nagaip-puk kiḍa-nāgum –ennai

Tanai-viḍaya mākka-viru tān-uṇḍō vonḍṛāi

Anai-varanu būdi uṇmai-yālōr – ninai-vaṛavē [33]

யொன்று முளத்து ளுணர்ந்துநிலை – நின்றிடா

துண்டின் றுருவருவென் றொன்றிரண் டன்றென்றே

சண்டையிடன் மாயைச் சழக்கொவொண்டியுளம் 34

Onḍ-ṛum uḷat-tuḷ uṇarndu-nilai – ninḍṛi-dādu

Uṇḍin ḍṛuru-varuven ḍṛon-ḍṛiran ḍan-ḍṛenḍṛē

Chaṇḍai-yiḍal māyaic chazhak-kozhiga – voṇḍi-yuḷam [34]

சித்தியெலாஞ் சொப்பனமார் சித்திகளே – நித்திரைவிட்

டோற்ந்தா லவைமெய்யோ வுண்மைநிலை நின்று பொய்மை

தீர்ந்தார் தியங்குவரோ தேர்ந்திருநீ – கூர்ந்துமயல் 35

Siddhi-yelāñ choppa-namār siddhigalē – niddirai-viṭṭu

Ōrndāl avai-meiyō uṇmai-nilai ninḍṛu-poimai

Tīrn-dār tiyaṅku-varō tērn-dirunī – kūrndu-mayal [35]

நாமதுவா நிற்பதற்கு நற்றயாமென்று

நாமதுவென் றேண்ணுவதே னான்மனித னெறெணுமோ

நாமதுவா நிற்குமத னாதேமுயலும் 36

Nām aduvā niṛpa-daṛku naṭṭṛu-naiyē – yāmen-ḍṛum

Nām-aduven ḍṛeṇ-ṇuvaḍē nān-manidan enḍṛe-ṇumō

Nām-aduvā niṛku-mada nāl-aṛiyā – dēmuyalum [36]

மோதுகின்ற வாதமது முண்வாதரவாய்த்

தான்றேடுங் காலுந் தனையடைந்த காலத்துந்

தான்றசம னன்றியார் தான்விபோன்ற 37

Ōdu-kinḍṛa vāda-madum uṇmai-yala – ādara-vāi

Tān-tēḍum kālum tanai-aḍainda kālat-tum

Tān-dasaman anḍṛi-yār tān-vittu – pōnḍṛa [37]

வினைமுதலா ரென்று வதனையறியக்

கர்த்தத் துவம்போய்க் கருமமூன் றுங்கழலு

நித்தமா முத்தி நிலமத்தனாய்ப் 38

Vinai-mudal āren-ḍṛu vinavi – tanai-yaṛiya

Kart-tattu vam-pōi karuma-mūndṛuṅ kazhalum

Nit-tamā mukti nilai-yīdē – matta-nāi [38]

பத்தனா ரென்றுதன்னைப் பார்க்குசித்தமாய்

நித்தமுத்தன் றானிற்க நிற்காதேற் பந்தசிந்தை

முத்திசிந்தை முன்னிற்கு மோகொத்தாங்கு 39

Battanā-renḍṛu tannaip-pārk-kuṅgāḷ – sittamāi

Nitta-muktan tāniṛka niṛkādēr bhanda-chindai

Muktti-chindai mun-niṛkumō manat-tukku – ottāngu [39]

முறுமுத்தி யென்னி லனுருவ –

மருவ முருவருவ மாயு மகந்தை

யுருவழிதன் முத்தி உதருள் ரமணன் 40

Uṛu-mukti ennil uraip-pan – uru-vam

Aru-vam uruvaru-vam āyum ahandai

Uru-vazhidan mukti uṇa-rīdu – aruḷ Ramaṇan [40]

Description

Ulladu Narpadu

Introduction by Sri Michael James

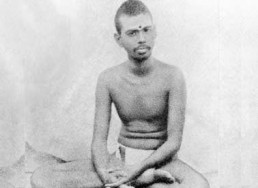

Ulladu Narpadu, the ‘Forty [Verses] on That Which Is’, is a Tamil poem that Sri Ramana composed in July and August 1928 when Sri Muruganar asked him to teach us the nature of the reality and the means by which we can attain it.

In the title of this poem, the word உள்ளது (ulladu) is a verbal noun that means ‘that which is’ or ‘being’ (either in the sense of ‘existence’ or in the sense of ‘existing’), and is an important term that is often used in spiritual or philosophical literature to denote ‘reality’, ‘truth’, ‘that which is real’ or ‘that which really is’. Hence in a spiritual context the meaning clearly implied by ulladu is atman, our ‘real self’ or ‘spirit’.

Though நாற்பது (narpadu) means ‘forty’, Ulladu Narpadu actually consists of a total of forty-two verses, two of which form the mangalam or ‘auspicious introduction’ and the remaining forty of which form the nul or main ‘text’.

Like many of his other works, Sri Ramana composed Ulladu Narpadu in a poetic metre called venba, which consists of four lines, with four feet in each of the first three lines and three feet in the last line, but since devotees used to do regular parayana or recitation of his works in his presence, he converted the forty-two verses of Ulladu Narpadu into a single verse in kalivenba metre by lengthening the third foot of the fourth line of each verse and adding a fourth foot to it, thereby linking it to the next verse and making it easy for devotees to remember the continuity while reciting.

Since the one-and-a-half feet that he thus added to the fourth line of each verse may contain one or more words, which are usually called the ‘link words’, they not only facilitate recitation but also enrich the meaning of either the preceding or the following verse.

In Bhagavan’s own words

The story of how the work Ulladu Narpadu came into being is told by Ramana Maharshi himself in Day by Day with Bhagavan, 7th December 1945:

Bhagavan referred to the article in the Vision of December, 1945 on Sthita Prajna and to the lines from Sat Darshana quoted in that article. Dr Syed thereupon asked Bhagavan when Reality in Forty Verses was made by Bhagavan. Bhagavan said, “It was recently something like 1928. Muruganar has noted down somewhere the different dates. One day Muruganar said that some stray verses composed by me now and then on various occasions should not be allowed to die, but should be collected together and some more added to them to bring the whole number to forty, and that the entire forty should be made into a book with a proper title. He accordingly gathered about thirty or less stanzas and requested me to make the rest to bring the total to forty. I did so, composing a few stanzas on different occasions as the mood came upon me.

When the number came up to forty, Muruganar went about deleting one after another of the old collection of thirty or less on the pretext they were not quite germane to the subject on hand or otherwise not quite suitable, and requesting me to make fresh ones in place of the deleted ones. When this process was over, and there were forty stanzas as required by Muruganar, I found that in the forty there were but two stanzas out of the old ones and all the rest had been newly composed. It was not made according to any set scheme, nor at a stretch, nor systematically. I composed different stanzas on different occasions and Muruganar and others afterwards arranged them in some order according to the thoughts expressed in them to give some appearance of connected and regular treatment of the subject, viz., Reality.” (The stanzas contained in the old collection and deleted by Muruganar were about twenty. These were afterwards added as a supplement to the above work and the Supplement too now contains 40 verses).

By Robert Butler

Sadhu Om, in his Sri Ramanopadesha Nunmali – Garland of Teaching Texts by Sri Ramana gives a detailed account of the process of creation outlined above, gleaned from his long acquaintanceship with Sri Muruganar, whose key role is mentioned in the above quotation. Sadhu Om first points out that, in 1923 when Muruganar first came to Ramana, little was known of Ramana’s true ‘teachings’ since he felt no compulsion either to speak or commit to writing anything of his own volition, preferring to allow his state to communicate itself to others through silence. What ‘teachings’ that were available were the results of his responses to individuals who had asked him questions and to whom he had replied, tailoring his answers to suit the specific philosophical standpoint of the questioner. (At this time the one existing work that adequately expresses Ramana’s advaitic standpoint, Nan Yar – Who am I, was not widely known).

According to Sadhu Om’s account, Muruganar was that rare one who humbly begged Ramana to ‘Pray tell what is the nature of reality, and how may it be attained, so that we may attain salvation!’ Muruganar’s pressing did not go unrewarded. Its fruits were two works of monumental importance, the Upadesha Undiyar, and Ulladu Narpadu. However, this is jumping ahead somewhat. Muruganar collated the occasional verses that Ramana had composed from time to time at the request of devotees, and proceeded, as Bhagavan describes, with his plan to make them into a book, bringing the number to 40, and then requesting Ramana to replace most of the original verses on the grounds that they were not suitable. His clear aim, as Ramana was no doubt well aware, was to eradicate anything that was not an authentic statement from his guru, and thus derive a work that was truly the teaching of his master. The number Forty was inspired by the title of several works on ethics from the early post- Classical period of Tamil literature, such as the Inna Narpadu, Forty on things which are harmful, and the Iniyavai Narpadu, Forty on things which are desirable. Like Ramana’s Ulladu Narpadu, both the aforementioned works were written in the venba metre, and it was clearly Muruganar’s aim to help create a work which recalled the great works of Tamil literature, rivalled them in its artistry and technical skill, and surpassed them in terms of its subject matter, Reality itself.

It should be added that, in Ulladu Narpadu, Ramana shows himself to be a true master of this most difficult and prized of metric forms. Accordingly therefore, according to Sadhu Om’s account, on the 21st July 1928, Ramana began composing one or two stanzas a day. Muruganar placed the new verses with the old ones in order according to subject matter, and whenever he felt that one or another of the old verses did not reflect the pure advaitic teaching of his master, he requested Ramana to compose a new one in its place, claiming that it was not sufficiently clear, or germane to the subject in hand. By August the 8th the work was complete. 19 new verses had been composed, 18 of the original 21 replaced, and a 2 line kural venba written as a Mangalam – Invocation.

Other Ramana Shlokams

Aksharamanamalai

Akshara mana malai means the Scented garland arranged alphabetically in praise of Arunachala. Composed by Bhagavan Ramana, Arunachala” literally means “Mountain of the colour of red.

Anma Viddai

Anma-Viddai (Atma Viddai), the ‘Science of Self’, also known as Atma-Vidya Kirtanam, the ‘Song on the Science of Self’, is a Tamil song that Sri Ramana Maharshi composed on 24th April 1927.

Appala Pattu

Bhagavan Ramana Maharshi composed the Appala Pattu or The Appalam Song when his mother Azhagammal came to live with him. Lyrics In Tamil, English, Telugu with Translation, Meaning, Commentary, Audio MP3 and Significance

Arunachala Ashtakam

Sri Arunachala Ashtakam means the ‘Eight Verses to Sri Arunachala’. It was composed by Sri Ramana Maharshi as a continuation of Sri Arunachala Patikam.

Arunachala Mahatmiyam

Arunachala Mahatmiyam Arunachala Mahatmiyam means the Glory of Arunachala - By Bhagavan Ramana Maharshi The following notes describe the greatness of Arunachala as gi

Arunachala Navamani Malai

Arunachala Navamani Malai means The Garland or Necklace of Nine Gems in praise of Sri Arunachala. This poem of nine verses was composed by Bhagavan Ramana Maharshi himself, in praise of Arunachala, the Lord of the Red Hill.

Arunachala Padigam

Sri Arunachala Padigam (Padhikam) means the ‘Eleven Verses to Sri Arunachala’. It was composed by Sri Ramana Maharshi after the opening words of the first verse, 'Karunaiyal ennai y-anda ni' had been persistently arising in his mind for several…

Arunachala Pancharatnam

Arunachala Pancharatnam Introduction by Sri Michael James Sri Arunachala Pancharatnam, the ‘Five Gems to Sri Arunachala’, is the only song in Sri Arunachala Stuti

Ekanma Panchakam

Ekanma Panchakam or Ekatma Panchakam means the ‘Five Verses on the Oneness of Self’, is a poem that Sri Ramana composed in February 1947, first in Telugu, then in Tamil, and later in Malayalam.

Ellam Ondre

Ellam Ondre - All Is One - Is a masterpiece by a Brahma Jnani Sri Vaiyai R Subramaniam about Advaita and path to attain the Unity. This book was highly recommended by Bhagavan Ramana Maharshi.

Saddarshanam

Saddarshanam is the Sanskrit Translation of Bhagavan Ramana Maharshi's Ulladu Narpadu, the Forty verses on Reality. The Tamil verses were translated into Sanskrit by Kavyakantha Ganapati Muni (Vasishta Ganapati Muni), who had also selected which…

Saddarshanam Telugu

This is the Telugu Transliteration of Saddarshanam from Sanskrit, which in turn is a translation of Bhagavan Ramana Maharshi's Ulladu Narpadu, The Forty on What Is.

The Path of Sri Ramana

The Path of Ramana, by Sri Sadhu Om, is a profound, lucid and masterly exposition of the spiritual teachings which Bhagavan Sri Ramana Maharshi graciously bestowed upon the world. The exact method of practicing the self-enquiry 'Who am I?' is…

Ulladu Narpadu – Explained

Ulladu Narpadu Introduction by Sri Michael James Ulladu Narpadu, the ‘Forty [Verses] on That Which Is’, is a Tamil poem that Sri Ramana composed in July and Au

Ulladu Narpadu Anubandham

Ulladu Nāṟpadu Anubandham, the ‘Supplement to Forty [Verses] on That Which Is’, is a collection of forty-one Tamil verses that Sri Ramana composed at various times during the 1920’s and 1930’s.

Ulladu Narpadu Anubandham Explained

Ulladu Nāṟpadu Anubandham along with Explanation by Sadhu Om: The ‘Supplement to Forty [Verses] on That Which Is’, is a collection of forty-one Tamil verses that Sri Ramana composed at various times during the 1920’s and 1930’s.

Ulladu Narpadu Kalivenba

Ulladu Narpadu Kalivenba - Also known as Upadēśa Kaliveṇbā is the extended (kalivenba) version of Ulladu Narpadu. Lyrics In Tamil, English, Telugu with Translation, Meaning, Commentary, Audio MP3 and Significance

Upadesa Saram

Upadesa Saram is the Sanskrit version of Upadesa Undiyar by Bhagavan Ramana Manarshi. First written in Tamil, this is a thirty-verse philosophical poem composed by Bhagavan Ramana Maharshi in 1927.

Upadesa Saram Telugu Transliteration

This is the Telugu transcription of Upadesa undiyar a Tamil poem of thirty verses that Sri Ramana composed in 1927 in answer to the request of Sri Muruganar, and that he later composed in Sanskrit, Telugu and Malayalam under the title Upadesa Saram,…

Upadesa Undiyar

Upadesa undiyar is a Tamil poem of thirty verses that Sri Ramana composed in 1927 in answer to the request of Sri Muruganar, and that he later composed in Sanskrit, Telugu and Malayalam under the title Upadesa Saram, the ‘Essence of Spiritual…

Works of Bhagavan Ramana

Compositions of Bhagavan Ramana Maharshi. In Tamil, English, Telugu, with Transliteration, Meaning, Explanatory Notes plus Audio. Includes Nan Yar, Ulladu Narpadu, Upadesa Undiyar, Upadesa Saram, Stuthi Panchakam and many more.

Ulladu Narpadu – Ramana – Lyrics In Tamil, English, Telugu with Translation, Meaning, Commentary, Audio MP3 and Significance