Swami Chinmayananda Commentary

When the meditator has thus practised meditation for a certain period of time, as a result of his practice, he comes to experience a larger share of quietude and peace in his mind. This extremely subtle form of inward peace is indicated here by the term “Prashanta.” This inward silence, a revelling in an atmosphere of extreme joy and contentment — is the exact situation in which the individual can be trained to express the nobler and the diviner qualities which are inherent in the Divine Self.

A meditator invariably finds it difficult to scale into the higher realms of experience due to sheer psychological fear-complex. As the Yogin slowly and steadily gets unwound from his sensuous vasanas, he gets released, as it were, from the cruel embrace of his own mental octopus. At this moment of transcendence, the unprepared seeker feels mortally afraid of the thought that he is getting himself dissolved into “NOTHINGNESS.” The ego, because of its long habit of living in close proximity to its own limitations, finds it hard even to believe that there is an Existence Supreme, Divine and Infinite. One is reminded of the story of the stranded fisher-women who complained that they could not get any sleep at all when they had to spend the night in a flower-shop, till they put their baskets very near their noses. Away from our pains, we dread to enter the Infinite Bliss!

This sense of fear is the death-knell of all spiritual progress. Even if progress were to reach the bosom of such an individual, he would be compelled to reject it, because of the rising storm of his subjective fear.

Even though the mind has become extremely peaceful and joyous, and has renounced all its sense of fear through the study of the Scriptures and continuous practice of regular meditation, the progress is not assured because the possibility of failure shall ever hang over the head of the seeker, unless he struggles hard to get established in perfect Brahmacharya.

THE ASCETICISM OF BRAHMACHARYA — Here the phrase implies not only its Upanishadic implications, but definitely something more original, especially when it comes from Lord Krishna’s mouth and that too, in the context of the Geeta. Brahmacharya, generally translated as ‘celibacy,’ has a particular meaning, but the term has also a wider and a more general implication. Brahmacharya is not ONLY the control of the sex-impulses but is also the practice of self-control in all avenues of sense-impulses and sense-satisfactions. Unless the seeker has built up a perfect cage of intelligent self-control, the entire world-of-objects will flood his bosom, to bring therein a state of unending chaos. A mind thus agitated by the inflow of sense stimuli, is a mind that is completely dissipated and ruined.

Apart from this meaning, which is essentially indicative of the goal, or rather, a state of complete detachment from the mind’s courtings of the external world-of-objects, there is a deeper implication to this significant and famous term. Brahmacharya, as such, is a term that can be dissolved in Sanskrit to mean “wandering in Brahma-Vichara.” To engage our mind in the contemplation of the Self, the Supreme Reality, is the saving factor that can really help us in withdrawing the mind from external objects.

The human mind must have one field or another to engage itself in. Unless it is given some inner field to meditate upon, it will not be in a position to retire from its extrovert pre-occupations. This is the secret behind all success in “total celibacy.” The successful Yogin need not be gazed at as a rare phenomenon in nature, for his success can be the success of all, only if they know how to establish themselves in this inward self-control. It is because people are ignorant of the positive methods to be practised for a continuous and successful negation and complete rejection of the charms of the sense-organs, that they invariably fail in their endeavour.

Naturally, it becomes easy for the individual who has gained in himself all the three above-mentioned qualities to control and direct the new-found energies in himself. The inward peace, an attribute of the intellect, comes only when the discriminative faculty is relatively quiet. Fearlessness brings about a great control over the exhausting thought commotions in the mental zone. Brahmacharya, in its aspect of sense-withdrawal, lends a larger share of physical quietude. Therefore, when, by the above process, the intellect, mind and body are all controlled and brought to the maximum amount of peace and quietude, the ‘way of life’ pursued by the seeker provides for him a large saving of mental energy which would otherwise have been spent away in sheer dissipation. This newly-discovered and fully availed-of strength makes the mind stronger and stronger, so that the seeker experiences in himself a growing capacity to withdraw his wandering mind unto himself and to fix his entire thoughts “in the contemplation of Me, the Self.”

The concluding instruction in this most significant verse in the chapter is: “LET HIM SIT IN YOGA HAVING ME AS HIS SUPREME GOAL.” It has been already said in an earlier chapter that the meditator should continue meditation, and ere long (achirena), he will have the fulfilment of his meditation. The same idea is suggested here. Having made the mind tame, and keeping it away from its own endless dissipations, we are instructed to keep the single-pointed mind in contemplation of the Divine Self and His Eternal Nature. Immediately following this instruction is the order that we should remain in this attitude of meditation, seeking nothing else but “ME AS THE SUPREME GOAL.” Ere long, in the silence and quietude within, the withering mind and other equipments will exhaust themselves, and the seeker will wake up to realise his own Infinite, Eternal, Blissful and quiet Nature, the Self.

Adi Sankara Commentary

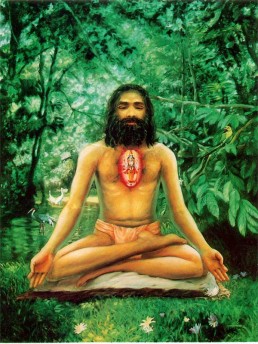

Dharayan, holding; kaya-siro-girvam, the body (torso), head and neck; samam, erect; and acalam, still-movement is possible for one (even while) holding these erect; therefore it is specified, ‘still’-; sthirah, being steady, i.e. remaining steady; sampreksya, looking svam nasikagram, at tip of his own nose -looking at it intently, as it were; ca, and; anavalokayan, not looking; disah, around, i.e. not glancing now and then in various directions-. The words ‘as it were’ are to be understood because what is intended here is not an injunction for looking at the tip of one’s own nose! What then? It is the fixing the gaze of the eyes by withdrawing it from external objects; and that is enjoined with a veiw to concentrating the mind. [What is sought to be presented here as the primary objective is the concentration of mind. If the gaze be directed outward, then it will result in interrupting that concentration. Therefore the purpose is to first fix the gaze of the eyes within.] If the intention were merely the looking at the tip of the nose, then the mind would remain fixed there itself, not on the Self! In, ‘Making the mind fixed in the Self’ (25), the Lord will speak of concentrating the mind verily on the Self. Therefore, owing to the missing word iva (as it were), it is merely the withdrawl of the gaze that is implied by sampreksya (looking). Further, prasantatma, with a placid mind, with a mind completely at peace; vigata-bhih, free from fear sthitah, firm; brahmacari-vrate, in the vow of a celibate, the vow cosisting in serivce of the teacher, eating food got by beggin, etc.-firm in that, i.e. he should follow these; besides, mat-cittah, with the mind fixed on Me who am the supreme God; samyamya, by controlling; manah, the mind, i.e. by stopping the modifications of the mind; yuktah, through concentration, i.e. by becoming concentrated; asita, he should remain seated; matparah, with Me as the supreme Goal. Some passionate person may have his mind on a woman, but he does not accept the woman as his supreme Goal. What then? He accepts the king or Sive as his goal. But this one (the yogi) not only has his mind on Me but has Me as his Goal. After that, now is being stated the result of Yoga:

The Bhagavad Gita with the commentary of Sri Sankaracharya – Translated by Alladi Mahadeva Sastry

Holy Geeta – Commentary by Swami Chinmayananda

The Bhagavad Gita by Eknath Easwaran – Best selling translation of the Bhagavad Gita

The Bhagavad Gita – Translation and Commentary by Swami Sivananda

Bhagavad Gita – Translation and Commentary by Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabupadha

Srimad Bhagavad Gita Chapter 6 – Verse 14 – 6.14 prasantatma vigatabhir – All Bhagavad Gita (Geeta) Verses in Sanskrit, English, Transliteration, Word Meaning, Translation, Audio, Shankara Bhashya, Adi Sankaracharya Commentary and Links to Videos by Swami Chinmayananda and others – 6-14