Gita Chapter 6 – Verse 47 « »

योगिनामपि सर्वेषां मद्गतेनान्तरात्मना ।

श्रद्धावान्भजते यो मां स मे युक्ततमो मतः ॥ ६-४७॥

ॐ तत्सदिति श्रीमद्भगवद्गीतासूपनिषत्सु

ब्रह्मविद्यायां योगशास्त्रे श्रीकृष्णार्जुनसंवादे

आत्मसंयमयोगो नाम षष्ठोऽध्यायः ॥ ६॥

yogināmapi sarveṣāṃ madgatenāntarātmanā

śraddhāvānbhajate yo māṃ sa me yuktatamo mataḥ 6-47

oṃ tatsaditi śrīmadbhagavadgītāsu upaniṣatsu

brahmavidyāyāṃ yogaśāstre śrīkṛṣṇārjunasaṃvāde

ātmasaṃyamayogo nāma ṣaṣṭho’dhyāyaḥ 6

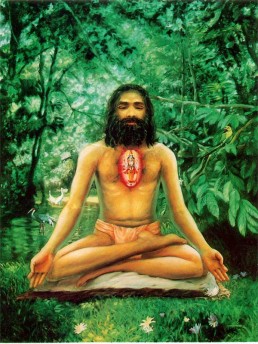

And among all YOGIS, he who, full of faith, with his inner-self merged in Me, worships Me, is, according to Me, the most devout.

yogināṃ = of yogis; api = also; sarveṣāṃ = all types of; madgatena = abiding in Me, always thinking of Me; antarātmanā = within himself; śraddhāvān = in full faith; bhajate = renders transcendental loving service; yaḥ = one who; māṃ = to Me (the Supreme Lord); saḥ = he; me = by Me; yuktatamaḥ = the greatest yogi; mataḥ = is considered.;