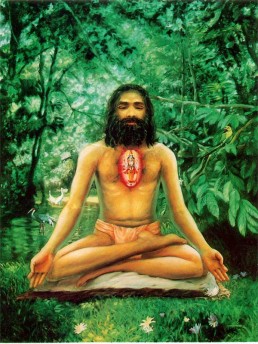

Swami Chinmayananda

Swami Chinmayananda Commentary

These four verses together give a complete picture of the state of Yoga and Krishna ends with a very powerful call to man that everyone should practise this Yoga of Meditation and self-development. In order to encourage man and make him walk this noble path of self-development and self-mastery, Bhagawan explains the goal which is gained by the meditator. When the mind is completely restrained, as explained in the above four stanzas, it attains a serene quietude and in that silence gains the experience of the Self, not as anything separate from itself, but as its own true nature.

This self-rediscovery of the mind, that is in fact nothing other than the Divine Conscious Principle, is the State of Infinite Bliss. This awakening to the cognition of the Self can take place only when the individual ego has smashed its limiting adjuncts and has thereby transcended its identifications with the body, mind and intellect.

That this bliss is not an objective experience such as is gained among the pleasures of the world, is evident by the qualification that it “transcends the senses” (Ati-indriyah). Ordinarily we gain our experiences in the world outside through our sense-organs. When the spiritual masters promise that Self-Realisation is a State of Bliss, we are tempted to accept it as an objective goal, but when they say that it is beyond the senses, the seekers start feeling that the promises of religion are mere bluff. The stanza, therefore, has to clearly insist that this Bliss of Self-recognition is perceivable only through the pure intellect.

A doubt may now arise that when, as a result of these almost super-human efforts, an individual has at last, come to experience this transcendental Bliss, it may provide only a flashy moment of intense living, which may then disappear, demanding, all over again, similar super-human efforts to regain one more similar moment of Bliss-experience. To remove this possible misunderstanding, the stanza insists: “ESTABLISHED WHEREIN, HE NEVER DEPARTS FROM HIS REAL STATE.” The Geeta repeatedly endorses that the experience of the Self is an enduring state from which there is no return. Even supposing one has gained this Infinite Bliss, will he not again come to all the sorrows that are natural to every worldly being? Will he not thereafter feel as great an urge as anyone else to strive and struggle, to earn and hoard, and thirst to love and be loved, etc.?

All these excitements which are carbuncles upon the shoulders of an imperfect man, are denied to a perfect one, as the following stanza (VI-22) explains the Supreme Truth as “HAVING COME TO WHICH NO ONE CAN CONSIDER ANY OTHER GAIN AS EQUAL TO IT, MUCH LESS EVER ANYTHING GREATER.”

Even after these explanations the Lord Himself raises the question which a man of doubts may entertain. It will be quite natural for a student, who is striving to understand Vedanta purely through his intellect, to doubt as to whether the experience of Divinity can be maintained, even during moments of stress and sorrow and in periods of misery and mourning. In other words: is not religion a mere luxury of the rich and the powerful, a superstitious satisfaction for the weak, a make-believe dream-heaven for the escapist? Can religion and its promised perfection stand unperturbed in all our challenges of life: bereavements, losses, illness, penury, starvation? This doubt — which is quite common in our times too — has been unequivocally answered here with a daring statement that “WHEREIN BEING ESTABLISHED ONE IS NOT MOVED EVEN BY THE HEAVIEST SORROW.”

To summarise: when by the quietude of the mind, gained through concentration, one comes to rediscover one’s own Self, his is the Bliss Absolute, which cannot be perceived through the senses and yet, can be lived, through a ‘pure intellect,’ and having reached which there is no more any return; having gained which there is no greater gain to strive for; and which is not shaken even by the lashings of the greatest tragedies of our existence. This is the wondrous Truth that has been indicated as the Self by the Geeta, the goal of all men of discrimination and spiritual aspirations.

This Self is to be known. The means of knowing this goal, as well as the state of its experience, is called “Yoga” in the Geeta. (VI — 23). Here we have one of the noblest, if revolutionary, definitions of Yoga.

We have explained earlier how the Geeta is an incomparable re-statement of the declaration of the Upanishads, in the context of the Hindu-world available at the time of the Mahabharata. The old idea that Yoga is a strange phenomenon, too difficult for the ordinary man to practise or to come to experience, has been remodelled here to a more tolerant and all-comprehensive definition. Yoga, which was till then a technique of religious self-perfection available only for a reserved few, has now been made a public park into which everyone can enter at his free will and entertain himself as best he can. In this sense of the term, the Geeta has been rightly called a revolutionary Bible of the Hindu Renaissance.

Apart from the divine prerogative of one who is an incarnation, we find a brilliant dash of revolutionary zeal in Krishna’s Godly personality both in His emotions and His actions. When such a divine revolutionary enters the fields of culture and spirituality, He could not have given a more spectacular definition of Yoga than that which He has given us here: “Yoga — a state of disunion from every union-with-pain.” This re-interpretation of Yoga not only provides us with a striking definition but at the same time, it is couched in such a clapping language of contradiction that it arrests the attention of every student and makes him think for himself.

The term “Yoga” means “contact.” To-day, man in his imperfection has contacts with only the world of finite objects and therefore, he ekes out of life only finite joys. These objects of the world are contacted through the instruments of man’s body, mind and intellect. Joy ended is the birth of sorrow. Therefore, life through the matter vestures is the life of pain-Yoga (dukha samyoga).

Detachment from this pain — Yoga is naturally a process in which we disconnect (Viyoga) ourselves from the fields of objects and their experiences. A total or even a partial divorce from the perceptions of the world of objects is not possible, as long as we are using the mechanism of perception, the organ of feeling, and the instrument of thinking. To get detached from the mechanism of perceptions, feelings and thoughts, would naturally be the total detachment from the pain-Yoga — (Dukha-Samyoga-Viyoga).

Existence of the mind is possible only through its attachment; the mind can never live without attaching itself to some object or other. Detachment from one object is possible for the mind only when it has attached itself to another. For the mind, detachment from pain caused by the unreal is possible only when it gets attached to the Bliss, that is the Nature of the Real. In this sense, the true Yoga — which is the seeking and establishing an enduring attachment with the Real — is gained only when the seeker cries a halt in his onward march towards pain, and deliberately takes a ‘right-about-turn’ to proceed towards the Real and the Permanent in himself. This wonderful idea has been most expressively brought out in the phrase which Bhagawan employs here, as a definition of Yoga — (Dukha-Samyoga-Viyoga).

A little scrutiny will enable us to realise that in defining Yoga thus, Sri Krishna has not introduced any new ideology into the stock of knowledge that was the traditional wealth of the Hindu scriptures. Till then, Yoga was emphasized from the standpoint of its goal, rather than from the exploration of its means. This over-emphasis of the goal had frightened the faithful followers away from its salutory blessings. And the technique of Yoga had sunk to become a mysterious and a very secret practice meant only for a few.

This Yoga is to be practised, insists Krishna, with “AN EAGER AND DECISIVE MIND.” To practise with firm resolve and an undespairing heart is the simple secret for the highest success in the practice of meditation, as the “Yoga with the Truth” is gained through a total successful “Viyoga from the false.”If we feel uncomfortably warm by being very near the fire-place we have only to move away from it to reach the cool and comforting atmosphere. Similarly, if, to live among the finite objects and live its limited joys is sorrow, thento get away from them is to enter into the Realm of Bliss which is the Self. This is “Yoga.

“FURTHER INSTRUCTIONS REGARDING YOGA ARE NOW CONTINUED AFTER THE ABOVE SHORT DIGRESSION. MOREOVER:

Adi Sankara Commentary

Vidyat, one should know; tat, that; duhkha-samyoga-viyogam, severance (viyoga) of contact (samyoga) with sorrow (duhkha); to be verily yoga-sanjnitam, what is called Yoga-i.e. oen should know it through a negative definition. After concluding the topic of the result of Yoga, the need for pursuing Yoga is again being spoken of in another way in order to enjoin ‘preservance’ and ‘freedom from depression’ as the disciplines for Yoga: Sah, that; yogah, Yoga, which has the results as stated above; yoktavyah, has to be practised; niscayena, with perservance; and anirvinnacetasa, with an undepressed heart. That which is not (a) depressed (nirvinnam) is anirvinnam. What is that? The heart. (One has to practise Yoga) with that heart which is free from depression. This is the meaning. Again,

The Bhagavad Gita with the commentary of Sri Sankaracharya – Translated by Alladi Mahadeva Sastry

Holy Geeta – Commentary by Swami Chinmayananda

The Bhagavad Gita by Eknath Easwaran – Best selling translation of the Bhagavad Gita

The Bhagavad Gita – Translation and Commentary by Swami Sivananda

Bhagavad Gita – Translation and Commentary by Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabupadha

Srimad Bhagavad Gita Chapter 6 – Verse 23 – 6.23 tam vidyad – All Bhagavad Gita (Geeta) Verses in Sanskrit, English, Transliteration, Word Meaning, Translation, Audio, Shankara Bhashya, Adi Sankaracharya Commentary and Links to Videos by Swami Chinmayananda and others – 6-23