Swami Chinmayananda

Swami Chinmayananda Commentary

In Vedantic literature, the Real and the Un-real are very scientifically distinguished. These two categories are not considered as indefinables in our ancient scriptures; though they do not declare these to be definables. The Rishis have clearly indicated what constitutes the REAL and what are the features of the UN-REAL. “That which was not in the past and which will not be in the future, but, that which seemingly exists only in the present is called the un-Real.” In the language of the Karika, “That which is non-existent in the beginning and in the end, is necessarily non-existent in the intermediate stages also; objects, we see, are illusory, still they are regarded as real.”

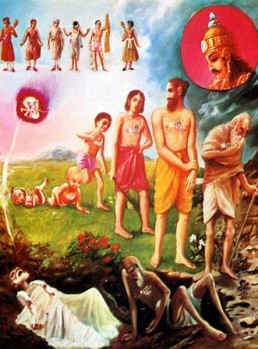

Naturally, the Real is “that which defies all changes and remains the same in all the periods of time: past, present and future.” Thus, in an ordinary example, when one misunderstands a post in the dark to be a ghost, the ghost-vision is considered unreal as compared to the post; because, the hallucination cannot be permanent and it does not remain after the re-discovery of the post. Similarly, on waking up from our dream, we do not get anxious to provide for our dream-children; because, as soon as we wake up, we realise that the dream was unreal. Before we went to bed, the dream-children were not with us, and after waking up, our dream-children are no more with us; thus we understand and realise that our dream-children, whom we loved and tended as real during our dream, are, in fact, unreal. By significance, therefore, the Real is that which exists at all times: in the past, the present and the future. The post is relatively real — it was, it is and it will be.

The life in our matter envelopments, we know, is finite, inasmuch as every little experience, at all the three levels of our existence — among the objects, with our sentiments, in the company of our ideas — in finite. The body changes at every moment; the mind evolves and the intellect grows. All changes, evolutionary movements and growths, are indicated by a constant-death of their previous state, in order that the thing concerned may change, evolve or grow. The body, the mind and the intellect are ever-changing in us, and all of them, therefore, according to our definition, cannot be Real.

But is there a Real entity behind it all? In order that change may take place, no doubt, a changeless substratum is necessary. For the waters of the river to flow, a motionless river-bed must exist. Similarly, in order to hold together the millions of experiences at the levels of our body, mind and intellect, and to give us the experience of a synchronised whole — which we call life — we must, necessarily, have some substratum, changeless and real, which is common to all three.

Something in us remains, as it were, unchanged all through our changes, holding the vivid experiences together as a thread holds the beads in a necklace. On closer analysis, it becomes clear that it can be nothing other than the Self in us, the Pure Awareness. Experiences that have come under one’s awareness do not constitute any vital aspect of one’s own Self; life is the sum total of experiences that have been devised by the touch of one’s illuminating Consciousness. In childhood, I was conscious of my childhood-life; in my youth, I was conscious of my youthful life; and in my old age, I am again conscious of my present experiences. The Consciousness remaining the same, endless experiences came under it, got illumined and died away. This Awareness by which I become conscious of things in my life — because of which I am considered as alive, but for which I will have no more existence in this given embodiment — “That” Spiritual Entity, Eternal and All-Pervading, Unborn and Undying, the One Changeless Factor, is the Infinite in me. And this Atman is the Real.

Men of knowledge and wisdom have known the essence, the meaning and the implication of both these: the Self and the non-Self, the Real and the Unreal, which in their mysterious combination constitute the strange phenomenon called the world.

WHAT THEN IS THAT WHICH IS EVER REAL? LISTEN:

Adi Sankara Commentary

Since ‘the unreal has no being,’ etc., for this reason also it is proper to bear cold, heat, etc. without becoming sorrowful or deluded. Asatah, of the unreal, of cold, heat, etc. together with their causes; na vidyate, there is no; bhavah, being, existence, reality; because heat, cold, etc. together with their causes are not substantially real when tested by means of proof. For they are changeful, and whatever is changeful is inconstant. As configurations like pot etc. are unreal since they are not perceived to be different from earth when tested by the eyes, so also are all changeful things unreal because they are not perceived to be different from their (material) causes, and also because they are not perceived before (their) origination and after destruction.

Objection: If it be that [Here Ast. has the additional words ‘karyasya ghatadeh, the effect, viz pot etc. (and)’.-Tr.] such (material) causes as earth etc. as also their causes are unreal since they are not perceived differently from their causes, in that case, may it not be urged that owing to the nonexistence of those (causes) there will arise the contingency of everything becoming unreal [An entity cannot be said to be unreal merely because it is non-different from its cause. Were it to be asserted as being unreal, then the cause also should be unreal, because there is no entity which is not subject to the law of cuase and effect.]?

Vedantin: No, for in all cases there is the experience of two awarenesses, viz the awareness of reality, and the awareness of unreality. [In all cases of perception two awarenesses are involved: one is invariable, and the other is variable. Since the variable is imagined on the invariable, therefore it is proved that there is something which is the substratum of all imagination, and which is neither a cause nor an effect.] That in relation to which the awareness does not change is real; that in relation to which it changes is unreal. Thus, since the distinction between the real and the unreal is dependent on awareness, therefore in all cases (of empirical experiences) everyone has two kinds of awarenesses with regard to the same substratum: (As for instance, the experiences) ‘The pot is real’, ‘The cloth is real’, ‘The elephant is real’ — (which experiences) are not like (that of) ‘A blue lotus’. [In the empirical experience, ‘A blue lotus’, there are two awarenesses concerned with two entities, viz the substance (lotus) and the quality (blueness). In the case of the experience, ‘The pot is real’, etc. the awarenesses are not concerned with substratum and qualities, but the awareness of pot,of cloth, etc. are superimposed on the awareness of ‘reality’, like that of ‘water’ in a mirage.] This is how it happens everywhere. [The coexistence of ‘reality’ and ‘pot’ etc. are valid only empirically — according to the non-dualists; whereas the coexistence of ‘blueness’ and ‘lotus’ is real according to the dualists.] Of these two awareness, the awareness of pot etc. is inconstant; and thus has it been shown above. But the awareness of reality is not (inconstant). Therefore the object of the awareness of pot etc. is unreal because of inconstancy; but not so the object of the awareness of reality, because of its constancy.

Objection: If it be argued that, since the awareness of pot also changes when the pot is destroyed, therefore the awareness of the pot’s reality is also changeful?

Vedantin: No, because in cloth etc. the awareness of reality is seen to persist. That awareness relates to the odjective (and not to the noun ‘pot’). For this reason also it is not destroyed. [This last sentence has been cited in the f.n. of A.A.-Tr.]

Objection: If it be argued that like the awareness of reality, the awareness of a pot also persists in other pots?

Vedantin: No, because that (awareness of pot) is not present in (the awareness of) a cloth etc.

Objection: May it not be that even the awareness of reality is not present in relation to a pot that has been destroyed?

Vedantin: No, because the noun is absent (there). Since the awareness of reality corresponds to the adjective (i.e. it is used adjectivelly), therefore, when the noun is missing there is no possibility of its (that awareness) being an adjective. So, to what should it relate? But, again, the awareness of reality (does not cease) with the absence of an object.. [Even when a pot is absent and the awareness of reality does not arise with regare to it, the awareness of reality persists in the region where the pot had existed. Some read nanu in place of na tu (‘But, again’). In that case, the first portion (No,…since…adjective. So,…relate?) is a statement of the Vedantin, and the Objection starts from nanu punah sadbuddheh, etc. so, the next Objection will run thus: ‘May it not be said that, when nouns like pot etc. are absent, the awareness of existence has no noun to qualify, and therefore it becomes impossible for it (the awareness of existence) to exist in the same substratum?’-Tr.]

Objection: May it not be said that, when nouns like pot etc. are absent, (the awareness of existence has no noun to qualify and therefore) it becomes impossible for it to exist in the same substratum? [The relationship of an adjective and a noun is seen between two real entities. Therefore, if the relationship between ‘pot’ and ‘reality’ be the same as between a noun and an adjective, then both of them will be real entities. So, the coexistence of reality with a non-pot does not stand to reason.]

Vedantin: No, because in such experiences as, ‘This water exists’, (which arises on seeing a mirage etc.) it is observed that there is a coexistence of two objects though one of them is non-existent. Therefore, asatah, of the unreal, viz body etc. and the dualities (heat, cold, etc.), together with their causes; na vidyate, there is no; bhavah, being. And similarly, satah, of the real, of the Self; na vidyate, there is no; abhavah, nonexistence, because It is constant everywhere. This is what we have said. Tu, but; antah, the nature, the conclusion (regarding the nature of the real and the unreal) that the Real is verily real, and the unreal is verily unreal; ubhayoh api, of both these indeed, of the Self and the non-Self, of the Real and the unreal, as explained above; drstah, has been realized thus; tattva-darsibhih, by the seers of Truth. Tat is a pronoun (Sarvanama, lit. name of all) which can be used with regard to all. And all is Brahman. And Its name is tat. The abstraction of tat is tattva, the true nature of Brahman. Those who are apt to realize this are tattva-darsinah, seers of Truth. Therefore, you too, by adopting the vision of the men of realization and giving up sorrow and delusion, forbear the dualities, heat, cold, etc. — some of which are definite in their nature, and others inconstant –, mentally being convinced that this (phenomenal world) is changeful, verily unreal and appears falsely like water in a mirage. This is the idea. What, again, is that reality which remains verily as the Real and surely for ever? This is being answered in, ‘But know That’, etc.

The Bhagavad Gita with the commentary of Sri Sankaracharya – Translated by Alladi Mahadeva Sastry

Holy Geeta – Commentary by Swami Chinmayananda

The Bhagavad Gita by Eknath Easwaran – Best selling translation of the Bhagavad Gita

The Bhagavad Gita – Translation and Commentary by Swami Sivananda

Bhagavad Gita – Translation and Commentary by Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabupadha

Srimad Bhagavad Gita Chapter 2 – Verse 16 – 2.16 nasato vidyate – All Bhagavad Gita (Geeta) Verses in Sanskrit, English, Transliteration, Word Meaning, Translation, Audio, Shankara Bhashya, Adi Sankaracharya Commentary and Links to Videos by Swami Chinmayananda and others – 2-16