Swami Chinmayananda

Swami Chinmayananda Commentary

In order to bring home to Arjuna the idea that the world, as experienced by an individual through the goggles of the mind-intellect-body, is different from what is perceived through the open windows of spirituality, this stanza is given. The metaphorical language of this verse is so complete in detail that the data-mongering modern intellect is not capable of entering into its poetic beauty. Of all the peoples of the world, the Aryans alone are capable of bringing about a combination of poetry and science, and when the poet-philosopher Vyasa takes up his pen, to pour out his art on to the ancient palmyra-leaves to express the Bliss of Perfection, in the ecstasy, he could not have used a better medium in the Geeta, than his poetry.

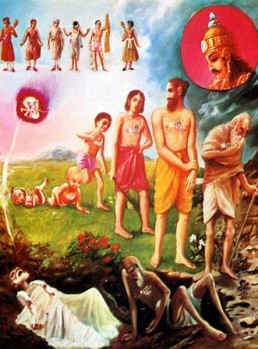

Here, two points-of-view — of the ignorant and of the wise — are contrasted. The ignorant person never perceives the world as it is; he always throws his own mental colour on to the objects and understands the imperfections in his mind to be a part and parcel of the objects perceived. The world, viewed through a coloured glass-pane, must look coloured. When this colouring medium is removed, the world appears AS IT IS.

The Consciousness in us is today capable of recognizing the world only through the media of the body, mind, and intellect. Naturally, we see the world imperfect, not because the world is so, but because of the ugliness of the media through which we perceive it.

A Master-mind is he who, rooted in his Wisdom, opens up the windows-of-his-perception and looks at the world through the eye-of-Wisdom.

When an electrical engineer comes to a city, and when at dusk, the whole city smiles forth with its lights, he immediately enquires: “Is it A. C. or D. C. current?”; while the same vision, to an illiterate villager, is a wondrous sight and he only exclaims: “I have seen lights that need no wick or oil!” From the stand-point of the villager, there is no electricity and no problem of A. C. or D. C. currents. The world the engineer sees among the very same lamps, is not realised or known by the unperceiving intellect of the villager. Nor is the engineer awake to the world of strange wonderment which the villager enjoys.

Here, we are told that the ego-centric, finite, mortal is asleep to the World-of-Perception enjoyed and lived by the Man-of-Steady-Wisdom; and that the Perfect One cannot see and feel the thrills and sobs which the ego experiences in its selfish life of finite-experience.

THE LORD PROCEEDS TO TEACH BY AN ILLUSTRATION THAT A WISE DEVOTEE ALONE, WHO HAS ABANDONED DESIRES AND WHOSE WISDOM IS STEADY, CAN ATTAIN MOKSHA, AND NOT HE WHO, WITHOUT RENOUNCING, CHERISHES DESIRES:

Adi Sankara Commentary

ya, that which; sarva-bhutanam, for all creatures; is nisa, night — which being darkness (tamah) by nature, obliterates distinctions among all things; what is that? that is the Reality which is the supreme Goal, accessible to the man of steady wisdom. As that which verily appears as day to the nocturnal creatures is night for others, similarly the Reality wich is the supreme Goal appears to be night, as it were, to all unenlightened beings who are comparable to the nocturnal creatures, because It is beyond the range of vision of those who are devoid of that wisdom. Samyami, the self-restrained man, whose organs are under control, i.e. the yogi [The man of realization.] who has arisen from the sleep of ignorance; jagarti, keeps awake; tasyam, in that (night) characterized as the Reality, the supreme Goal. That night of ignorance, characterized by the distinctions of subjects and objects, yasyam in which; bhutani, the creatures, who are really asleep; are said to be jagrati, keeping awake, in which night they are like dreamers in sleep; sa nisa, it is night; pasyatah, to the seeing; muneh, sage, who perceives the Reality that is the supreme Goal, because that (night) is ignorance by nature. Therefore, rites and duties are enjoined only during the state of ignorance, not in the state of enlightenment. For, when Knowledge dawns, ignorance becomes eradicated like the darkness of night after sun-rise. [It may be argued that even after illumination the phenomenal world, though it is known to be false, will continue to be perceived because of the persistence of past impressions; therefore there is scope for the validity of the scriptural injunctions even in the case of an illumined soul. The answer is that there will be no scope for the injunctions, because the man of realization will then have no ardent leaning towards this differentiated phenomenal world which makes an injunction relevant.] Before the rise of Knowledge, ignorance, accepted as a valid means of knowledge and presenting itself in the different forms of actions, means and results, becomes the cause of all rites and duties. It cannot reasonably become the source of rites and duties (after Realization) when it is understood as an invalid means of knowledge. For an agent becomes engaged in actions when he has the idea, ‘Actions have been enjoined as a duty for me by the Vedas, which are a valid means of knowledge’; but not when he understands that ‘all this is mere ignorance, like the night’. Again, the man to whom has come the Knowledge that all these differences in their totality are mere ignorance like the night, to that man who has realized the Self, there is eligibility only for renouncing all actions, not for engaging in actions. In accordance with this the Lord will show in the verse, ‘Those who have their intellect absorbed in That, whose Self is That’ (5.17) etc., that he has competence only for steadfastness in Knowledge.

Objection: May it not be argued that, there will be no reason for being engaged even in that (steadfastness in Knowledge) if there be no valid means of knowledge [Vedic injunctions.] to impel one to that. [Because, without an injunction nobody would engage in a duty, much less in steadfastness to Knowledge.] Answer: No, since ‘knowledge of the Self’ relates to one’s own Self. Indeed, by the very fact that It is the Self, and since the validity of all the means of knowledge culminates in It, [The validity of all the means of knowledge holds good only so long as the knowledge of the Self has not arisen.] therefore the Self does not depend on an injunction to impel It towards Itself. [Does the injunction relate to the knowledge of the Self. or to the Self Itself? The first alternative is untenable because a valid means of knowledge reveals its objects even without an injunction. The second alternative also is untenable because the Self is self-revealing, whereas an injunction is possible in the case of something yet to be achieved. And one’s own Self is not an object of that kind.] Surely, after the realization of the true nature of the Self, there is no scope again for any means to, or end of, knowledge. The last valid means of (Self-) knowledge eradicates the possibility of the Self’s becoming a perceiver. And even as it eradicates, it loses its own authoritativeness, in the same way as the means of knowledge which is valid in dream becomes unauthoritative during the waking state. In the world, too, after the preception of an abject, the valid means of that perception is not seen to be a cause impelling the knower (to any action with regard to that object). Hence, it is established that, for an knower of the Self, there remains no eligibility for rites and duties. The attainment of Liberation is only for the sannyasin [Liberation is attained only by one who, after acquiring an intellectual knowledge of the Self in a general way, is endowed with discrimination and detachment, has arisen above all desires, has become a monk in the primary sense, and has directly realized the Self by going through the process of sravana (understanding of Upanisadic texts about the Self), etc.], the man of enlightenment, who has renounced all desires and is a man of steady wisdom; but not for him who has not renounced and is desirious of the objects (of the senses). Such being the case, with a view to establishing this with the help of an illustration, the Lord says:

The Bhagavad Gita with the commentary of Sri Sankaracharya – Translated by Alladi Mahadeva Sastry

Holy Geeta – Commentary by Swami Chinmayananda

The Bhagavad Gita by Eknath Easwaran – Best selling translation of the Bhagavad Gita

The Bhagavad Gita – Translation and Commentary by Swami Sivananda

Bhagavad Gita – Translation and Commentary by Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabupadha

Srimad Bhagavad Gita Chapter 2 – Verse 69 – 2.69 ya nisha – All Bhagavad Gita (Geeta) Verses in Sanskrit, English, Transliteration, Word Meaning, Translation, Audio, Shankara Bhashya, Adi Sankaracharya Commentary and Links to Videos by Swami Chinmayananda and others – 2-69