Swami Chinmayananda Commentary

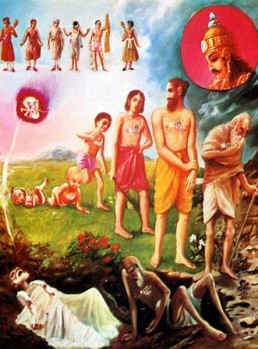

One who has an evenness of temper accomplished by his perfect withdrawal from the realm of sentiments and emotions, and who is established in his resolute intellect, gets himself transported from the arena of both the good and the bad, merit and de-merit. The conception of good and bad is essentially of the mind, and the reactions of merit and de-merit are left on the mental composition in the form of Vasanas or samskaras. He, who is not identifying with the stormy sea of the mind, will not be thrown up or sunk down by the huge waves of Vasanas. This idea is explained here by the term Buddhi yuktah: one whose actions are all guided by his clear vision of his higher and diviner Goal.

The Geeta, throughout this section, is sincerely calling upon man not to live on the outskirts of his personality, which are constituted of the worlds of sense-objects, the physical body and the mind, but to enter into the realm of the intellect, and from there to assert his natural manliness. Man is the supreme creature in the kingdom of the living, because of the rational capacities of his discriminative intellect. As long as man does not utilise this special equipment in him, so long he cannot claim his heritage as man.

Arjuna was asked by Krishna not to be a vain and hysterical person, but to be a he-man and, therefore, ever a master of all his external situations. The great hero, Arjuna, became so frail and weak because he started living in delusory identification with the sense of his own physical security and with his various emotional attachments.

He who lives constantly asserting his full evolutionary status as man, becomes free from the chains and bondages of all his past impressions (vasanas), which he must have gathered in his pilgrimage through his different embodiments.”Therefore, apply yourself,” advises Krishna, “to the devotion of action, Yoga.” In this context, again, Vyasa is giving a definition of Yoga, as he means it here. Earlier, he had already explained that “Evenness of mind is Yoga.” Now he re-writes the same definition more comprehensively and says, “Yoga is dexterity in action.”

In a science-book, if the very same term is defined differently in every chapter, it would bring about confusion in its understanding. How is it then that in the Science of Religion, we find different definitions of the same term? This riddle solves itself as soon as we carefully attempt an intimate understanding of the definition. The earlier definition is being incorporated in the latter one, because, otherwise, “evenness of mind is Yoga” may be misunderstood as a mere ‘evenness of mind’ producing inaction and slothfulness. In this definition such a misunderstanding is completely removed, and thus Karma Yoga, as indicated in the all-comprehensive meaning implied herein, indicates the art of working with perfect mental equilibrium in all the different conditions indicated by the term “pairs-of-opposites” (Dwandwas).

After dissecting this stanza thus, we come to understand what exactly is the Lord’s intention. When Yoga, “the art of working without desire,” is pursued, the Karma Yogin becomes detached from all the existing vasanas in himself, both good and bad. The vasana-pressure in the individual causes restlessness within. The inner-equipment that has become peaceful and serene is called the pure Antah-Karana, which is an unavoidable prerequisite for consistent, discriminative self-application in meditation. Thus all actions, when properly pursued, become means for the ultimate end of realising the Self through meditation, with a pure mind.

We have here yet another example of Vyasa using the frightening word Yoga in a tamer context in order to make his society then feel at ease with it.

WHY SHOULD WE CULTIVATE THIS EVENNESS OF MIND AND CONSEQUENTLY AN EXTRA DEXTERITY IN ACTION?

Adi Sankara Commentary

Listen to the result that one possessed of the wisdom of equanimity attains by performing one’s own duties: Buddhi-yuktah, possessed of wisdom, possessed of the wisdom of equanimity; since one jahati, rejects; iha, here, in this world; ubhe, both; sukrta-duskrte, virtue and vice (righteousness and unrighteousness), through the purification of the mind and acquisition of Knowledge; tasmat, therefore; yujyasva, devote yourself; yogaya, to (Karma-) yoga, the wisdom of equanimity. For Yoga is kausalam, skilfulness; karmasu, in action. Skilfulness means the attitude of the skilful, the wisdom of equanimity with regard to one’s success and failure while engaged in actions (karma) — called one’s own duties (sva-dharma) — with the mind dedicated to God. That indeed is skilfulness which, through equanimity, makes actions that by their very nature bind give up their nature! Therefore, be you devoted to the wisdom of equanimity.

The Bhagavad Gita with the commentary of Sri Sankaracharya – Translated by Alladi Mahadeva Sastry

Holy Geeta – Commentary by Swami Chinmayananda

The Bhagavad Gita by Eknath Easwaran – Best selling translation of the Bhagavad Gita

The Bhagavad Gita – Translation and Commentary by Swami Sivananda

Bhagavad Gita – Translation and Commentary by Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabupadha

Srimad Bhagavad Gita Chapter 2 – Verse 50 – 2.50 buddhi-yukto – All Bhagavad Gita (Geeta) Verses in Sanskrit, English, Transliteration, Word Meaning, Translation, Audio, Shankara Bhashya, Adi Sankaracharya Commentary and Links to Videos by Swami Chinmayananda and others – 2-50